The Pechenegs are one of the many steppe peoples who have lived in the Euro-Asiatic steppes through history. By the end of the 9th century, they occupied areas east of the River Volga and north of the Caspian and the Aral Sea. As a recognizable community, they are mentioned for the first time in the report of an Uighur envoy as a people neighboring similar communities – Cumans, Kipchaks, Kimäks – who spoke the type of Turkic language such as the Pechenegs (Pálóczi Horváth 1989, 11).

Just like other steppe peoples, the base of Pecheneg warfare was cavalry. They mostly avoided close combat if they were not sure of the possibility of breaking enemy lines. Their armies were mostly made of light troops, the main weapons of which were the bow with flat arrows and the spear. According to the composition of the troops, the typical tactic of the Pechenegs was the so called feigned retreat and ambush. In the case of close combat, they usually have carried a secondary weapon – a mace, a small axe or a saber. However, hand-to-hand combat was not a characteristic of nomad armies, especially against the heavily armed forces of the Roman Empire or Kievan Rus’. The Pechenegs have avoided direct attacks on cities and fortresses. Instead, sieges were carried out by starving such places to surrender (Pálóczi Horváth 1989, 18).

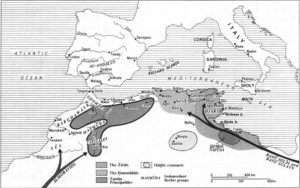

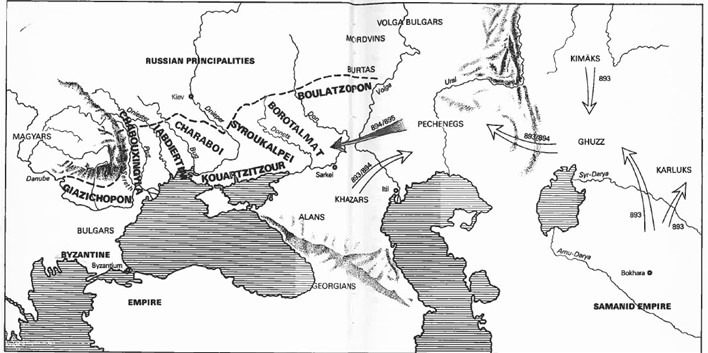

The last decade of the 9th century is marked by the migration of the Pechenegs to the west. In the year 893, emir Ismail ibn-Ahmed, the second ruler of the Samanid dynasty, recently established in the region around the Amu-Darja and Sir-Darja Rivers, began a campaign against his steppe neighbors. This was primarily directed against the Turkic Ghuzz, who were defeated and forced to retreat to the west. After the defeat, the Ghuzz entered into an alliance with the Khazars and attacked the Pechenegs with the rest of their forces. So the Pechenegs lost their pastures and most of the livestock they were breeding. They were forced to move further westward. In this migration, they came into contact with the Hungarians, whom they pushed to the west with the help of the Bulgarians, who at that time were hostile to the Hungarians. These events caused a domino effect, which moved the ethnic and linguistic image of the Eurasian steppes deeper towards Europe. With the success against the Hungarians, the period of century and a half of Pecheneg domination began on the territory of the Black Sea steppes (Pálóczi Horváth 1989, 11-12). At the same time, the Hungarians settle in Pannonia and Moravia, from where they will, under the Arpad dynasty, invade Central and Western Europe and eventually establish their own kingdom (Beckwith 2009, 165).

The newly acquired Pecheneg territory stretched from the border of the Khazar Empire, Middle Don and Volga to the north and east and to the Carpathians and the Lower Danube to the west. The Pechenegs were not a uniformed people, but a group of tribes. According to the information provided by Roman Emperor Constantine VII Porphyrogenitus in the 10th century, the Pechenegs were a confederation of eight tribes – Giazichipon, Chabouxingyla, Iabdiertim, Charaboi, Kouartzitzour, Syroukalpei, Borotalmat and Boulatzopon (Pálóczi Horváth 1989, 12). During the next century and a half the tribal system described by Constantine VII was gradually transformed with the population growth, detachment of some clans and the arrival of others from the east. By the mid-eleventh century we find 13 Pecheneg hordes (Pálóczi Horváth 1989, 15-16).

By settling in the Black Sea steppes the Pechenegs found themselves in a strategic position between the regional powers – the Roman Empire, Bulgaria, Kievan Rus’ and Hungary. In such surroundings they will be an active and important factor in the relationships between neighboring forces, often changing sides (Pálóczi Horváth 1989, 16).

***

The 10th century was the era of Pecheneg domination in the Black Sea steppes. Their position determined their relations with the surrounding forces. In the north, the Pechenegs bordered the Kievan Rus’. Since the beginning of the century, the two communities have maintained a relatively peaceful coexistence, basing it on trade. The Rus’ benefited from cattle bred by the Pechenegs, buying it for towing and transport. On the other hand, the Pechenegs imported grain from the Kievan Rus’, which was not very widespread in their predominantly herder society. The Pechenegs were even involved in some Rus’ campaigns against neighboring countries, such as the invasion of the Roman Empire in 944. Rus’ sought to maintain peaceful relations with the Pechenegs not only because of their trade, but also because of the trade with the Roman Empire. The vast territory that was occupied by the Pechenegs between the Kievan Rus’ and the Roman Empire could not be overcome in hostile circumstances (Martin 2007, 19). However, as early as the mid-10th century, relations between the Rus’ and the Pechenegs were getting worse. The Pechenegs began to plunder the border regions of Kievan Rus’ and the trade route on the Dnieper River used by the Rus’ to trade in the south, especially with the Roman Empire (Martin 2007, 20).

In 968 the Roman Emperor Nikephoros II Phokas encouraged the Kievan Prince Sviatoslav to attack Bulgaria, the bitter adversary of the Roman Empire. However, Sviatoslav showed intentions of staying in the south, on the territory of defeated Bulgaria. With that, the Roman Empire got an even more dangerous neighbor than the Bulgarian Emperor was. Thus in the year 971 the war between Sviatoslav and the new Roman Emperor John Tzimiskes has begun. The outcome was uncertain as long as the following year when the Pechenegs ambushed and killed Prince Sviatoslav by the Dnieper Rapids. Reportedly, they made a drinking cup from Sviatoslav’s skull, according to the custom of the many steppe peoples. By killing Sviatoslav, the Pechenegs liberated the Roman Empire from a great threat (Shepard 2006, 61-62).

Further deterioration of the relationship between the Pechenegs and the Rus’ followed in the time of the Kievan Prince Vladimir, especially after he converted to Christianity. Vladimir thus bound his state to the Roman Empire and so it became necessary to secure the roads from Kiev to Constantinople. In such circumstances, the Pechenegs became increasingly aggressive. At the end of the century, the Pechenegs launched a few great incursions into Rus’ territory, precisely in the years 992, 995 and 997. In the year 996, after a great defeat, Vladimir himself nearly fell into the hands of the Pechenegs. However, he managed to gather a new army in Novgorod in the north and continue with the conflict. The war between the Pechenegs and Kievan Rus’ lasted until Vladimir’s death in 1015. His son Boris will continue fighting with the Pechenegs shortly, but will soon be killed by his brother, an event that initiated dynastic struggles in Kievan Rus’. During the course of Vladimir’s rule, the Pechenegs were pushed somewhat southward, but not so far from Rus’ territory that they would not be able to get into Rus’ political issues. Some Pecheneg groups, who served as the auxiliary forces of Kievan Rus’, participated in the aforementioned war for Vladimir’s legacy. However, Pecheneg attacks on Rus’ lands at this time generally wane (Martin 2007, 20-21). The Pechenegs attacked Kiev in 1036 for the last time and were defeated by Prince Jaroslav under the city walls. This defeat marked the end of the Pecheneg threat to the lands of the Rus’ (Martin 2007, 53). Their relationship with the Rus’ countries became somewhat passive. In the middle of the 11th century, at the time of Pechenegs’ re-movement towards the west, the Kievan Prince Vsevolod launched two attacks against them, in 1055 and 1060 (Martin 2007, 54).

During the 12th century, the name Black Caps was used by the Rus’ for nomadic border guards considered to be consisted of, among other peoples, the remains of Pechenegs (Pálóczi Horváth 1989, 26).

***

Shortly after arriving in the Black Sea steppes, the Pechenegs became the subject of Roman politics and their principle divide et impera. Despite being potential Roman allies, at the same time they represented a threat to Roman territory, particularly the Cherson theme. The Roman Empire tended to balance between potential allies, depending on the relationship of neighboring forces to it. When the Kievan Rus’, with victory over Bulgaria, became a dangerous threat to the boundaries of the Empire, in the year 968, the Roman Emperor Nikephoros II Phokas encouraged the Pechenegs to attack the Rus’ lands. The Pechenegs, as we have mentioned, had a major role in ending the war between the Romans and the Rus’ in 971. Thus, the Roman policy largely determined decisions and movements of neighboring peoples, including the Pechenegs (Madgearu 2013, 207-208). In the time of the great Roman Emperor Basil II, the Pechenegs as Roman clients maintained the balance of power in the Black Sea steppes (Angold 2008, 585). After this period of alliances, there came the period marked by the hostile relationship between the Pechenegs and the Roman Empire. In 1017, the recovered Bulgarian Empire invoked the Pechenegs in the war against the Roman Empire. The Pechenegs have not yet crossed the Danube to begin with the overt hostility, but a decade later they launched an open invasion on the Roman European themes. In 1032, many of the Roman fortifications on the Danube and the interior of the theme of Dristra were attacked in series of incursions. Such relations lasted until 1036, when the Empire initiated a peace agreement with the Pechenegs, which allowed undisturbed trade across the Danube. To the Roman Empire, which was weakened by plunder and war, unobstructed trade was crucial to maintain economic stability (Madgearu 2013, 208-209).

A few years later, turbulences continued. The Pechenegs were displaced from the Black Sea steppes by the Ghuzz from the east. In the winter of 1046-7, the majority of Pechenegs crossed the Danube, seeking refuge on Roman soil. Roman Emperor Constantine IX has unsuccessfully sent his forces against the arriving Pechenegs. The outcome was that the Pechenegs occupied much of the Roman Balkans. Constantine IX, however, partially took over the situation by recruiting a part of the Pechenegs and sending their detachments to the eastern border, where the Seljuk Turks were pressing against the Roman border (Angold 2008, 599-600). Some of the Pecheneg leaders accepted Christianity, thus joining the Roman system (Madgearu 2013, 212).

As subjects of the Roman Empire, the Pechenegs proved themselves extremely unreliable. In the battle of Manzikert in 1071, we find the Pechenegs deserting to the Seljuk side (Madgearu 2013, 218). The next conflict between the Pechenegs and the Romans was a decade and a half later, when the Emperor Alexios I Komnenos tried to regain the Danube border. In 1086 the Emperor suffered a defeat in a sudden Pecheneg attack on his forces. The Pechenegs found an ally in Tzachas, a Seljuk emir who had held Smyrna and turned it into a pirate base. In 1091 Alexios lead a new and inexperienced army toward the port of Ainos, hoping to prevent the unification of the Pechenegs and their Seljuk ally. Salvation to the Roman forces was brought by the Cumans, who originally intended to co-operate with the Pechenegs, but Alexios managed to win them over to his side. Thus the Romans and the Cumans decisively defeated the Pechenegs in the battle of Levounion (Angold 2008, 611-612).

The last assault on the Roman Empire by the Pechenegs was undertaken in 1122. They were heavily defeated by the Emperor John II Komnenos and forcibly settled in various parts of the Balkans, where they will gradually assimilate to the local population (Pálóczi Horváth 1989, 26). Other remnants of the Pechenegs will inhabit the lands of the Rus’ and, as remains to be seen, among the Hungarians.

***

From the first contact of the Pechenegs with the Hungarians, we find mutual relationship between the two peoples. They were not so intense during the 10th century, although a part of the Pecheneg dignitaries who entered the territory of the Hungarians in those times undoubtedly participated in the creation of the Hungarian kingdom. Penetration of the Pechenegs towards the Pannonian Basin in the 11th century, where the Hungarian Kingdom was formed, inevitably caused the increase of mutual relationship between them. Already in the first half of the 11th century we find smaller contingents of the Pechenegs in the Hungarian army (Pálóczi Horváth 1989, 31).

After mid-11th century, the Black Sea steppes were briefly dominated by the Ghuzz, followed by longer Cuman domination. Therefore, the Pechenegs and other, lesser communities were being pushed to the edges of the steppe, towards the borders of the neighboring states. Thus comes the first major influx of the Pechenegs across the borders of the Hungarian kingdom. However, this could not be compared with the pressure of the Pechenegs on the Roman border, but there was a clear increase in the number of Pecheneg warriors in the Hungarian army. The smaller concentration of the Pechenegs on the territory of Hungarians compared to the Roman Empire diminished the possibility of an open rebellion of the Pecheneg troops, which was the case in the Roman Empire. Autonomous position of the Pechenegs on the Lower Danube was suddenly cut by the defeat from Alexios Komnenos in 1091. After this defeat, the remnants of the Pechenegs scatter towards the Rus’ states and Hungary. After the unsuccessful invasion of the Roman Empire in 1122, one group of the Pechenegs requested shelter at the court of King Stephen II of Hungary (Pálóczi Horváth 1989, 31).

The Pechenegs left very few traces of their original steppe culture in Hungary. The earliest Pecheneg groups came when both communities were still pagan, and they received Christianity together with the Hungarian rulers. At the time of the greater influx of the Pechenegs, Christianity was already firmly established in the Hungarian kingdom. Therefore, newcomers were forced to adapt to the circumstances and baptize themselves. Although the Pechenegs may have remained a recognizable group for some time, they will eventually become assimilated to the population of Hungary (Pálóczi Horváth 1989, 38).

Bibliography:

Angold, Michael. 2008. ”Belle époque or crisis? (1025–1118).” In The Cambridge History of the Byzantine Empire c. 500-1492, edited by Jonathan Shepard, 583-626. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Beckwith, Christopher I. 2009. Empires of the Silk Road: A History of Central Eurasia from the Bronze Age to the Present. Princeton, Oxford: Princeton University Press.

Madgearu, Alexandru. 2013. ”The Pechenegs in the Byzantine Army.” In The Steppe Lands and the World Beyond Them, Studies in honor of Victor Spinei on his 70th birthday, edited by Florin Curta, Bogdan-Petru Maleon, 207-218. Iaşi: Editura Universității “Alexandru Ioan Cuza”.

Martin, Janet. 2007. Medieval Russia 980-1584. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Pálóczi Horváth, András. 1989. Pechenegs, Cumans, Iasians: Steppe peoples in medieval Hungary. Budapest: Corvina.

Shepard, Jonathan. 2006. ”The Origins of Rus’.” In The Cambridge History of Russia, volume 1, From Early Rus’ to 1689, edited by Maureen Perrie, 47-72. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Velmans, Tania. 1983. ”Three Notes on Miniatures in the Chronicle of Manasses.” In Macedonian Studies Quarterly Journal (1): 25-54.

Web sources:

World Digital Library. n. d. ” History of Byzantium” Accessed February 21, 2019. https://dl.wdl.org/10625/service/10625.pdf

Autor:

Recenzenti:

- Dominik Pešut, voditelj projekta, voditelj recenzijskog tima;

- Mihaela Marić, članica recenzijskog tima;

- Ivan Grkeš, član recenzijskog tima.

Ovaj esej objavljen je u Anno Domini Enciklopediji, dijelu međunarodnog projekta Anno Domini, na gromovnik.hr – mrežnoj stranici Udruge “Gromovnik”.