The Cumans were a nomadic people of Turkic origin and the last of the steppe peoples that migrated from Central Asia to Europe before the Mongol invasion. We can include their westward journey in the same wave of nomadic raids from Central Asia which started with the Hungarian tribes. The Pechenegs, Ghuzz, and Cumans followed the same route, but Hungarians already established their own state that was a barrier between incoming nomadic peoples and Latin Europe (Drobný 2012, 205).

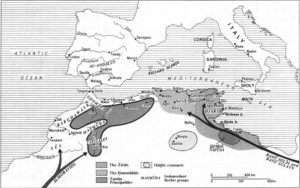

By the 1030s, the confederation of the nomadic Kipchaks dominated the vast areas of what is today the Kazak steppe, the Ghuzz people occupied the territory between the Ural and the Volga rivers, and the Pechenegs inhabited grasslands from the Volga to the Lower Danube, including the steppe region of what is now Ukraine, Moldavia and Wallachia (Vásáry 2005, 4). Simultaneously, around the middle of the 11th century, a new nomadic people of the Pontic steppe – the Cumans – emerge in Roman sources. The Cumans and the Kipchaks were originally two separate peoples, but around the mentioned time they formed a tribal confederation and jointly progressed westwards. By the twelfth century, the Cumans and the Kipchaks merged in the process of cultural and political amalgamation. By the late twelfth century their appellations – Qipčaq, Quman together with their translations, such as Polovec, Valwe, Xarteš etc. – became interchangeable. They labeled the whole confederation (Vásáry 2005, 5-6). Further in the text we will use the term Cumans to designate the Cuman-Kipchak confederation.

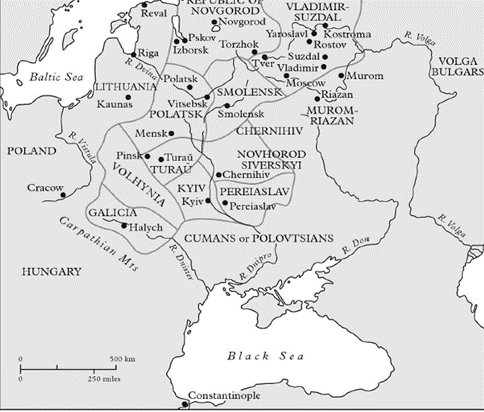

There was no firm political entity such as a Cuman empire, but different Cuman tribes with their own rulers, who acted independently of other chieftains (or khans). They interfered with the policies of surrounding states, such as the Rus’ principalities or the Roman Empire. The vast area inhabited by the Cumans was called variously in sources of different origins – Dašt-i Qipčaq (Kipchak steppes) by Muslim authors, Zemlja Poloveckaja (Polovician Land) in Russian, and Cumania in Latin sources (Vásáry 2005, 7).

Some of the Cuman tribal centers can be located using the Russian sources’ valuable information and via archaeology. Comparing these allows us to envisage the distribution of the tribes throughout the Black Sea steppes. At the end of the eleventh and the beginning of the twelfth century, most political power was concentrated in the hands of the tribes that inhabited areas west of the Dnieper. These western parts of the confederation were the most important in regional politics, initiating plundering campaigns into territories of the Roman Empire, Rus’ principalities, Hungary and Poland (Pálóczi Horváth 1989, 43-44).

Written sources and archaeological finds attest great differences in the wealth and social status of the members of the Cuman society. The wealth and political power of the aristocracy were underpinned by members of the warrior-class, called nögers or nökörs in the language of the Cumans. We also find latter as mercenaries in service of foreign states, including Georgia, Serbia, Bulgaria, and later Hungary (Pálóczi Horváth 1989, 45). The Cuman economy was, in accordance with their nomadic lifestyle, primarily based on animal husbandry. With time, some of them settled permanently on acquired territory, so they became prone to land cultivation. The Cuman lands were crossed by important trade routes, so they received the opportunity to join the trade and tribute network with other regional powers. Raiding was also one of the basic sources of income for the nomadic Cumans. Their war and plundering activities were chiefly based on horsemanship. Contemporary sources in their descriptions of Cumans emphasize how skilled they were as horsemen (Lyublyanovics 2015, 16-18).

There was internal unrest in the Cuman confederation – separation attempts of individual tribes and growth of chieftains’ power at the expense of their Khan. During the first half of the 12th century, these turmoils led to the splitting of the Cuman confederation into the western and the eastern branch, bordering at the line of the Dnieper. Arabic geographer Idris mentions territories of White and Black Cumania, probably referring to the mentioned parting. The eastern Cuman branch covered a much larger territory, freely stretching into the steppes toward Central Asia (Pálóczi Horváth 1989, 44-45). Such state of affairs came to an end by the end of the twelfth century, when Könchek Khan, who was leading the eastern Cumans, re-united the two branches. With that, there was an opportunity to unite all Cumans under a central authority, possibly to create some kind of political entity that could be designated by the term empire. However, Könchek Khan and his successors were not decisive enough in their policy to crush the power of the tribes, clans and their leaders. Thus, they were unable to raise a compact and concentrated military force needed to secure the potential state and its institutions. Also, Könchek’s and succeeding efforts came too late – they were thwarted by the supervenient Mongol invasion that threatened the very survival of the Cuman people (Pálóczi Horváth 1989, 45).

***

From the mid-11th century until the Mongol invasion in the 13th century the Cumans inhabited the region of the Black Sea steppes and played an important role in regional politics. Their migration was part of a massive nomadic migration wave to the West, probably caused by the expansion of the Khitan Empire which occupied mostly areas of modern-day Manchuria and Mongolia (Lyublyanovics 2015, 12). In the 1050s the Cumans pressed Ghuzz tribes further westward and arrived on the southern frontier of Rus’ principalities. Attenuation of Ghuzz military power left the way open for the Cumans. In 1068, the Cuman force was strengthened even more by the inflicted defeat on a coalition of forces led by the Kievan prince Iziaslav I Iaroslavich. After this victory, the Cumans controlled the vast area between the Aral Lake and the Lower Danube (Spinei 2009, 117).

The year 1078 is the date of the first Cuman raid into the Balkans, towards Roman territory. From this time the Cumans were actively present on the Danube frontier (Curta 2006, 306). In the late 1080s, they joined the Pecheneg and Hungarian forces in a joint incursion in the Roman Balkan provinces. The disagreement between the Cumans and the Pechenegs regarding plunder shares caused split-up between the two nomad peoples. Roman Emperor Alexius I knew how to skillfully exploit the mentioned breach. In the spring of 1091, he managed to defeat the Pechenegs with the decisive support of the Cumans in the battle of Levounion (Spinei 2009, 120). However, the Cumans proved to be unreliable allies. Only a few weeks after the defeat of the Pechenegs, they invaded the Balkans as Roman rule was jeopardized in Dalmatia. There are no direct clashes mentioned between the imperial army and the Cuman invaders, so it is probable that the marauders returned to their residences north of the Danube before encountering the Roman army. In 1091 or the year later, after their return from the plundering of Roman provinces, the Cumans launched another raid, this time into Transylvania and Hungary. Their incursion was soon thwarted by the Hungarian King Ladislas (Spinei 2009, 120-121).

After the period of incursions into the Roman and Hungarian territories, the subject of Cuman invading interest shifted to the Rus’ regions around the Middle Dnieper. They reinitiated their raids against the Rus’ in 1092, plundering their lands along with the territories of the Kingdom of Poland (Spinei 2009, 121). On the other side, we find the Cuman army as allies of princes in south-western Rus’, led by the Kievan great prince Sviatopolk II, against the Hungarian king Coloman. In this campaign, the Cuman attack wiped out the Hungarian forces. A few years later, in 1106, we find the recurrent Cuman incursion into Rus’ territory repelled by their relatively recent ally Sviatopolk II (Spinei 2009, 123-124).

Alexius I utilized the lull in the Cuman-Roman relationship by recruiting Cuman mercenaries to firmly secure the Danube frontier, in particular on the occasion of the crusaders’ passing through the Balkans in 1096 and 1097 (Spinei 2009, 123). For twenty-five years there were no troubles with Cuman intrusions, which indicates Comnenian efforts to ensure the protection of the northern frontier of the Empire. John II Comnenus, just like his father Alexius, strived to maintain peace with the Cumans, given the circumstances in which the imperial armies were engaged in conflicts, among others, against the Seljuq Turks, the Normans and the Hungarians (Spinei 2009, 127). At the same time, the Cumans had problems with the Kievan great prince Vladimir II Monomakh, who led several campaigns against them in their steppe abodes. Thus Vladimir prevented them from plundering other regions. After his death in 1125, the Cumans were free to initiate new campaigns and thus influence political stability in the regions surrounding the Black Sea steppes. After Vladimir’s death, the open struggles between various Rus’ princes began, so the Cumans seized the opportunity and began to interfere in the conflicts to weaken their northern neighbors. In 1135 the Cumans initiated an invasion of the Rus’ lands, while also plundering Polish territory (Spinei 2009, 127-128).

After Manuel I Comnenus ascended to the throne in 1143, Roman relations with the Cumans have rapidly deteriorated. In 1148, the new period of Cuman plundering campaigns began. In the following years there were multiple incursions of the Cumans into Roman lands, but before long they retreated north of the Danube. After this raid, the Cumans did not invade Roman territories south of the Danube anymore. Presumably, an agreement was achieved between the Cumans and Manuel I (Spinei 2009, 128-130).

***

It seems that the Cumans were on hold during the 1160s, when the Emperor’s armies operated unhampered in the areas north of the Danube (Curta 2006, 316). During the last two decades before the collapse of the Empire in the Fourth Crusade, the Cumans were again an active factor in Roman politics. In 1186 they assisted the Vlach rebels, Peter and Asen, against Emperor Isaac. In the final years before the Empire’s fall, the Cumans are mentioned, independently or jointly with Vlach or Rus’ allies, several times attacking the weakened Empire and plundering its Balkan territories (Curta 2006, 317).

By the end of the 12th century, Christianity was introduced to the Cumans and even more after, at the beginning of the 13th century, mendicant orders began their missionary activity in the lands beyond western Christianity (Lyublyanovics 2015, 29). Few decades before the Mongolian invasion, the Dominicans began their missions in Cuman lands. After initial failures, they made a great success in 1227, when the Khan of the Cumans west of the Dnieper, had himself and his people baptized and swore allegiance to the Hungarian king (Pálóczi Horváth 1989, 48).

First decades of the 13th century were marked by the ominous approach of the Mongol hordes. The Cumans just began showing first overt signs of adaptation and incorporation into the western civilizational system, when the mortal threat came from the east. They suffered their first defeat against the Mongols in 1223, at the battle of the Kalka River, together with their Rus’ allies. In 1241, the Cuman confederation came to an end as a political entity. Its tribes were either dispersed among surrounding peoples or became subject to the new conquerors (Vásáry 2005, 9).

Bibliography:

Curta, Florin. 2006. Southeastern Europe in the Middle Ages 500-1250. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Drobný, Jaroslav. 2012. ”Cumans and Kipchaks: Between Ethnonym and Toponym.” Zbornik Filozofickej Fakulty University Komenskeho, Graecolatina et Orientalia XXXIII – XXXIV: 205-217.

Lyublyanovics, Kyra. 2015. ”The Socio-Economic Integration of Cumans in Medieval Hungary. An Archaeozoological Approach.” PhD diss., Central European University, Budapest.

Pálóczi Horváth, András. 1989. Pechenegs, Cumans, Iasians: Steppe peoples in medieval Hungary. Budapest: Corvina.

Plokhy, Serhii. 2015. The Gates of Europe: A History of Ukraine. New York: Basic Books

Spinei, Victor. 2009. The Romanians and the Turkic Nomads North of the Danube Delta from the Tenth to the Mid-Thirteenth Century. Leiden, London: Brill. Vásáry, István. 2005. Cumans and Tatars, Oriental Military in the pre-Ottoman Balkans, 1185-1365. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Autor:

Recenzenti:

- Dominik Pešut, voditelj projekta, voditelj recenzijskog tima;

- Mihaela Marić, članica recenzijskog tima;

- Ivan Grkeš, član recenzijskog tima.

Ovaj esej objavljen je u Anno Domini Enciklopediji, dijelu međunarodnog projekta Anno Domini, na gromovnik.hr – mrežnoj stranici Udruge “Gromovnik”.